On March 24 2020, #GeneralStrike was among Twitter’s most prominent hashtags in response to calls that people return to work just days after social distancing measures and lockdowns were put in place to lessen COVID-19’s effects and spread.

Related hashtags trended, among them: #NotDying4WallStreet, #COVIDIDIOTS, #BernieIsOurFDR, #DieForTheDow, and #StayAtHomeOrder. Here’s what led up to it:

What started all this?

On March 20 2020, California and New York State both announced wide-scale “lockdowns” or “stay at home orders,” restrictions on non-essential movements aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19. A release issued by New York State Gov. Andrew Cuomo explained the parameters of that order:

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo [on March 20 2020] announced he is signing the “New York State on PAUSE” executive order, a 10-point policy to assure uniform safety for everyone. It includes a new directive that all non-essential businesses statewide must close in-office personnel functions effective at 8PM on Sunday, March 22, and temporarily bans all non-essential gatherings of individuals of any size for any reason.

In all, sixteen states (including California and New York) ordered its residents to stay home for all but essential activity — health care work, grocery store operation, and mail delivery among them. An additional nine states maintained partial restrictions, either jurisdictionally or involving lighter restrictions:

This means at least 163 million people in 17 states, 14 counties and eight cities [were] being urged to stay home.

People [could] generally still leave their homes for necessities — to go to the grocery store, to go to the doctor and to get fresh air. Still, the changes so fundamentally alter American life that some states have been hesitant to adopt them. Some — Maryland and Kentucky, for example — have walked up to the line, closing down all non-essential businesses and verbally asking people to be safe at home. Others described the decision as agonizing but necessary.

Why did so many states act at once?

On March 17 2020, an Imperial College London paper released one day earlier received widespread attention; it is broadly speculated that the information it presented in part informed the urgency and abrupt nature of restrictions undertaken in states in the United States and outside the country.

In short, researchers projected outcomes for various approaches to mitigate the global spread of COVID-19. Under all models, deeply upsetting trajectories ended with mass mortality numbering millions in the United States alone.

One strategy — called “suppression” in the paper — dramatically slashed those mortality rates. However, it involved a very long-term set of restrictions, fully in place until September 2020 and partly in place until September 2021. Those projections were predicated on part on the expected introduction of a coronavirus vaccine for SARS-nCoV-2.

So scientists talked, and (some) states listened. What’s the problem?

On March 22 2020, about 48 hours into New York and California’s lockdowns, United States President Donald Trump sent the following tweet at 10:50 PM:

Trump’s use of all-caps suggested a focused intent on ending “stay at home” measures as quickly as possible. That afternoon, Trump addressed reporters, reiterating his belief that the economy was far more important than the millions of lives at stake:

President Donald Trump on [March 23 2020] said he planned to pull the U.S. economy out of its coronavirus-induced slumber in a matter of weeks, and refused to commit to following the advice of his handpicked health experts — many of whom have warned that it will be a matter of months before it will be safe to reopen the country again — when reassessing guidelines for social isolation.

“Our country wasn’t built to be shut down. This is not a country that was built for this,” Trump insisted to reporters during a White House press briefing with his coronavirus task force on [March 23 2020], predicting that “America will again and soon be open for business. Very soon. A lot sooner than three or four months that somebody was suggesting.”

Slate.com published an article on the subject of whether abandoning social distancing measures would circumvent the economic effects of COVID-19 (to say nothing of the social costs):

This is an extremely dangerous line of thinking, and not just because it will likely lead to more casualties. Encouraging Americans back to work before the virus is contained will not save the economy from catastrophe. Rather, it will set the country up to limp along, half-functioning as the pandemic spreads further … Let’s recall why public health officials have asked Americans to stay home in the first place. It’s not because COVID-19 is incredibly deadly (though it does appear to be more fatal than the flu). Rather, it’s because the new coronavirus is so highly contagious that if even a small percentage of the people who stand to be infected end up hospitalized, it will completely swamp our health care system, as already seems to be happening in New York. If even 20 percent of Americans catch this thing in the next year—which is the sort of best-case scenario researchers are envisioning—vast swaths of the country will run out of hospital beds.

[…]

Many people will not return to their normal lives in a country that is being ravaged by an unchecked disease just because the president has announced a “reopening.” Many aren’t going to return to restaurants and bars or go on family vacations to Disney. Many companies aren’t going to tell their employees to come back to the office. Many cities and states will keep businesses shut down in order to try to contain the illness as much as possible within their own borders. But some won’t. And many Americans will try to resume life as usual, the same way many are ignoring the warnings to stay in now, which means the virus will continue spreading. We will have a half-functioning economy and nonfunctioning health care system, with untold numbers of Americans dying from an illness that causes victims to suffocate as fluid floods into their lungs, on the way to total organ failure.

Trump continued addressing the measures via Twitter on March 23 2020, emphasizing a return to work — and a lifting of restrictions on person-to-person contact:

So was the debate about the economy?

Not exactly.

Discussions about the length of stay at home orders tended to be couched in the terms Trump used — “Americans want to go back to work” or “the economy cannot sustain …” — typically questioning whether the economic cost of such measures were worth the efforts to soften the effects of the pandemic.

But not everyone hewed to purely fiscal framing. Lt. Gov. of Texas Dan Patrick engaged in what is often called “saying the quiet part out loud” when he appeared to outright assert that the Baby Boomer generation ought to absorb the mortality rate:

On Twitter, Patrick shared the Fox News segment in which he made the remarks:

The Dallas Morning News quoted Patrick’s interview, in which “sacrifice” was used at least once in terms of “sacrificing the economy” versus COVID-19’s risks to health and infrastructure:

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick said [on March 23 2020 that] the country should go back to work in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. And the Republican suggested “grandparents” such as he — at higher risk of contracting severe cases of COVID-19 — should sacrifice to keep the country out of economic trouble.

“My message is that let’s get back to work. Let’s get back to living. Let’s be smart about it,” Patrick told Fox News host Tucker Carlson. “And those of us who are 70 plus, we’ll take care of ourselves. But don’t sacrifice the country.”

The message echoed remarks by President Donald Trump on Monday. Trump said he wants to reopen the country for business in weeks, not months — as he claimed, without evidence, that continued closures could result in more deaths than the pandemic itself.

It appeared Patrick did actually muse that Americans over 70 could “take care of” themselves as he urged all citizens not to “sacrifice” the economy over COVID-19 suppression measures. (Patrick is 69 years old as of March 24 2020.)

How did social media react to Trump’s remarks and Patrick’s interview?

As noted several questions above, #NotDying4WallStreet, #COVIDIDIOTS, #BernieIsOurFDR, #DieForTheDow, and #StayAtHomeOrder were among the top ten trending hashtags the morning after Patrick’s Fox News interview on March 23 2020.

At first glance, #ReOpenAmerica seemed to be a hashtag in support of ending stay at home orders. But a quick browse of top tweets there indicated it too was largely opposition to lifting coronavirus lockdowns:

What is a general strike?

As stated above, workers deemed “nonessential” in sixteen states were subject to “stay at home” orders starting March 20 2020. Workers in other states were in some instances under lockdown orders, but a balance of states observed no such restrictions.

A general strike stretches across industries, and most (if not all) workers participate in order to achieve specific objectives, whether economic or political. Teen Vogue addressed the concept in a January 2019 explainer:

A general strike is a labor action in which a significant amount of workers from a number of different industries who comprise a majority of the total labor force within a particular city, region, or country come together to take collective action. Organized strikes are generally called by labor union leadership, but they impact more than just those in the union

[…]

Though the concept has its roots in ancient Rome’s secessio plebis [withdrawal of the plebian class], one of the first modern general strikes took place during the Industrial Revolution in Northern England in 1842, a time of great civil and social unrest, as modern capitalism began to take hold and hierarchical class lines began to be drawn between employers and employees. General strikes played pivotal roles in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Spanish Civil War. And in the U.S., general strikes became almost common during the 19th and early 20th centuries, with examples taking hold in Philadelphia (1835), St. Louis (1877), Chicago (1886), New Orleans (1892), and Seattle (1919), and during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. These large-scale actions were instrumental in securing crucial workers’ rights that many of us take for granted today, from basic safety regulations to the eight-hour workday and the end of child labor. But those wins did not come easily.

What would that look like?

This:

Who was making demands, why were they making demands, and what was being negotiated by lawmakers?

A number of ancillary issues around the pandemic involved the severity and length of the necessary suppression measures needed (such as long-term closure of schools and non-essential business) and how Americans could make ends meet under such extraordinary conditions.

Democrats and Republicans debated the terms of relief offered; as of March 24 2020, the parties remained locked in talks regarding the specifics of economic relief:

Democrats have repeatedly blocked efforts to advance the [proposed] stimulus because of concerns that it prioritizes corporate industry over American workers. Republicans have argued that Democrats are stalling critical economic relief amid the devastating spread of coronavirus.

On March 23 2020, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi issued a press release explaining Democrats’ proposals in the ongoing negotiations. Sen. Bernie Sanders, also campaigning for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, called for more specific protections (including $2000 a month payments to everyone for the duration of the pandemic):

Cover all health care treatment for free, including coronavirus testing, treatment, and the eventual vaccine. Under this proposal, Medicare will ensure that everyone in America, regardless of existing coverage, can receive the health care they need during this crisis. We cannot live in a nation where if you have the money you get the treatment you need to survive, but if you’re working class or poor you get to the end of the line. That is morally unacceptable.

[…]

Keep workers on payroll. Small and medium sized businesses, especially those in severely impacted industries such as restaurants, bars, and local retail need immediate relief. We must tell these businesses, who are being forced to lay off their entire staff or possibly even shut down through no fault of their own, that we will not allow them to go out of business. The federal government will work with affected businesses to provide direct payroll costs for small and medium sized businesses to keep workers employed until this crisis has passed.

We will provide all necessary assistance, including tax deferrals, utility payment suspension, rental assistance, affordable loans, and eviction protection for struggling businesses. When this crisis passes, we will be ready to start our economy up again without the risk of losing the stores and restaurants integral to our communities. None of this financial assistance shall be used for executive bonuses, stock buybacks or profiteering.

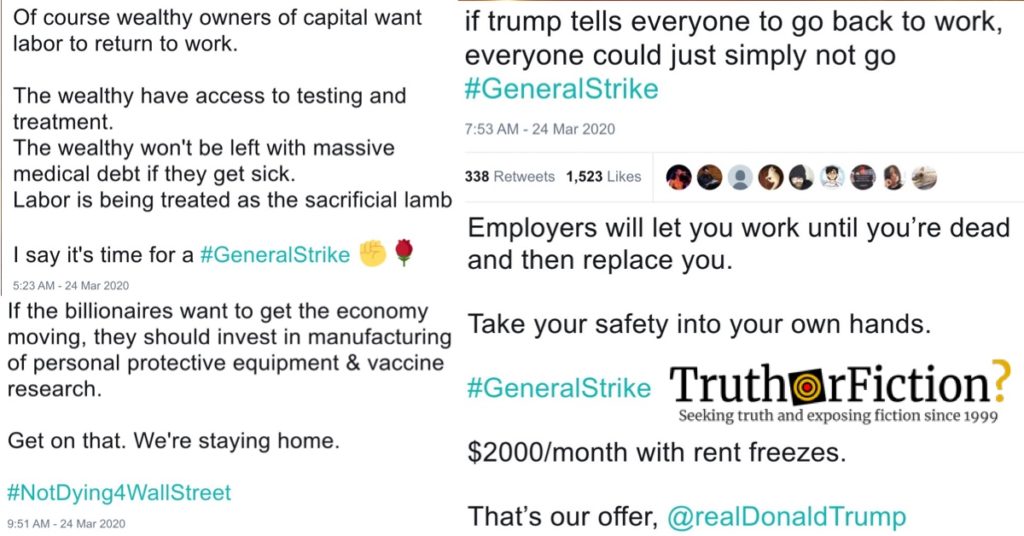

What did #GeneralStrike tweets look like?

As talks among lawmakers in Congress stalled, social media users and candidates called for a variety of measures to maintain COVID-19 prevention measures, while lambasting industry:

Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich didn’t explicitly call for a general strike, but shared a thread along the same lines:

What were the specific aims of a proposed general strike?

They varied, but typically monthly payments of $2,000 to $4,000 a month per family, COVID-19 health care coverage for all (even the uninsured), a freeze on mortgage or rent payments, student loan relief, and related efforts to offset the financial effects of extended “stay at home” orders:

Or simply:

What are the stakes?

The early days of pandemics are decisive, as evidenced by early reports coming out of Wuhan, China, where COVID-19 was first identified:

Most estimates of COVID-19’s potential death rate were high — and those didn’t include secondary deaths due to an overwhelmed health care system (long ambulance waits, gaps in critical care for events like cardiac arrest):

Is a general strike likely if workers are asked to return to work in March 2020?

A frequently-mentioned element of the coronavirus pandemic is its unprecedented nature. Americans have lived through pandemics, economic downturns, and crises of leadership — but rarely all at once.

As the New York Observer reported, organized strikes have been effective. The circumstances triggered by COVID-19 were unique, but it also seemed American workers had reached a tipping point in their frustrations:

“I’d die for my family. I’d die for my friends. However, if these sons of bitches think that I’m gonna die to keep rich assholes rich, they’re dead wrong,” read one popular tweet.

“We need a mass general strike if the grotesque ghouls in our government decide it’s good for everyone to go back to work & risk their lives when all of our hospitals are far over capacity & there aren’t enough ventilators,” read another. “Fuck you, we’re #NotDying4WallStreet.”

Put simply: people are angry. They’re angry that they’re getting sick. They’re angry that it took several weeks for the U.S. to even acknowledge that this was a crisis. They’re angry that Trump fired the U.S. pandemic response team that could have taken action when it was clear what we were dealing with… Successful strikes can lead to major wins for labor. The U.S. Postal Service Strike of 1970, the country’s first nationwide strike of public employees, was an eight-day “wildcat strike” (that is, an illegal strike taken without approval of union leadership) that led to the formation of the modern American postal service and won the employees their full collective bargaining rights. Today, the American Postal Workers Union is the largest in the world, representing 200,000 employees, and the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970 defined the USPS as “a basic and fundamental service” provided to all Americans.

The Observer story also noted that the atypical circumstances included a workforce already spread thin (both before and due to COVID-19), possibly past a point where direct action was avoidable. Many Americans were already financially devastated by the pandemic, left with less to lose by engaging in preventive measures like a general strike:

The fact is that workers are already being hurt, whether they’re dying from the pandemic itself or figuring out how to account for lost wages. Those calling for a #GeneralStrike and #NotDying4WallStreet have indicated that they prefer the pain of our economy being squeezed to the pain of an out-of-control virus killing them or their loved ones. The question that remain is how quickly one can or will be organized.

So many examples of direct action — such as a general strike — are from decades ago. Could such a thing happen in 2020?

It happened in France in December 2019 and January 2020, due to widespread opposition to pension reforms:

France’s biggest strike in decades has shut down public transport services and reduced the number of hospital staff, teachers and police officers at work in the latest protest against President Emmanuel Macron’s reforms.

In this case, unions representing millions of staff in both the public and private sectors are unhappy about a plan to overhaul the country’s pension system, which they say will force people to work longer or face reduced payouts when they retire.

One opinion poll put public support for the latest strike action at 69%, with backing strongest among 18-34 year-olds.

TL;DR: What’s actually going to happen?

Social media users overwhelmingly expressed opinions that proposals involving a return to work placed profits over lives, and the more explicit calls to specifically endanger older Americans in order to “save the economy” were particularly poorly received. Lawmakers remained stalled in attempts to introduce comprehensive economic measures to sustain working Americans during extended quarantines, and more and more people reported immediate financial hardship by the day.

The outcome of increased demand for a general strike remained to be seen, although tensions over calls to end lockdowns after just two days continuing rising. As of March 24 2020, both positions — one calling for all workers to return to work, and another encouraging direct action — were proposed, but not organized.

Update, April 15 2020: For additional information on the current status of coronavirus stimulus payments, or if your deposit has not arrived, please visit:

- #NotDying4WallStreet

- #COVIDIDIOTS

- #BernieIsOurFDR

- #DieForTheDow

- #StayAtHomeOrder

- How Coronavirus Lockdown Will Affect California's Economy

- Governor Cuomo Signs the 'New York State on PAUSE' Executive Order

- See Which States and Cities Have Told Residents to Stay at Home

- Imperial College London’s COVID-19 Report, Explained

- ‘Our country wasn’t built to be shut down’: Trump pushes back against health experts

- Sending People Back to Work Now Will Not Save the Economy. It Will Doom It.

- Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick spurns shelter in place, urges return to work, says grandparents should sacrifice

- General Strike

- General Strike

- Everything You Need to Know About General Strikes

- After four days of marathon negotiating, still no stimulus deal in the Senate

- Pelosi Statement Ahead of Unveiling of Democrats’ Third Coronavirus Response Bill

- An Emergency Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Coronavirus Drives Calls for a General Strike and #NotDying4WallStreet

- Macron pension reform: Why are French workers on strike?