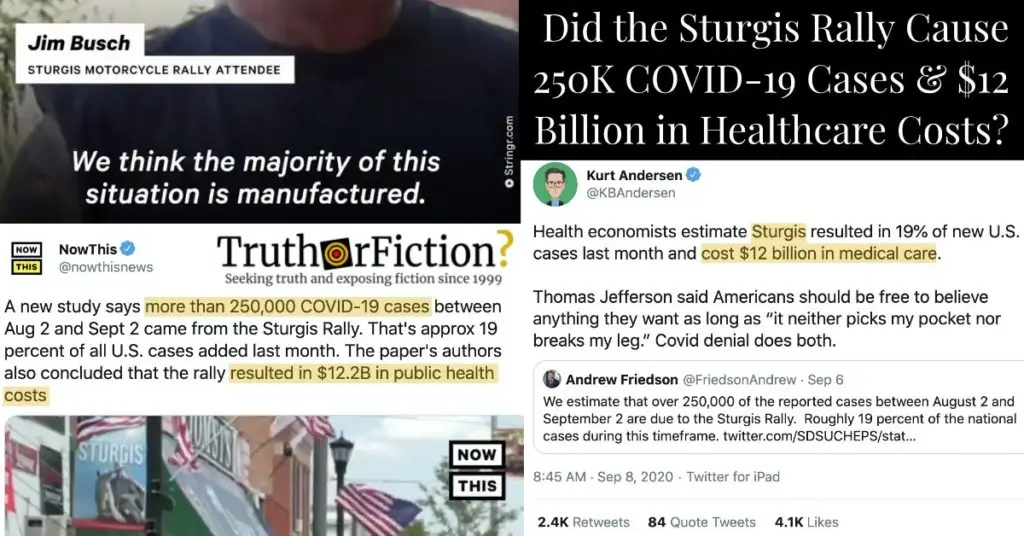

September 8 2020 marked approximately one month from the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota, and it heralded purported news that the widely-attended gathering served as a “super-spreader event” during an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic:

The above tweet said:

A new study says more than 250,000 COVID-19 cases between Aug 2 and Sept 2 [2020] came from the Sturgis Rally. That’s approx 19 percent of all U.S. cases added last month. The paper’s authors also concluded that the rally resulted in $12.2B in public health costs

Other Tweets

As “Sturgis” trended on Twitter, many users shared commentary about a new, albeit unconfirmed, study:

Sturgis Motorcycle Rally

The event took place from August 6 to August 17 2020. A FAQ on the official page estimated a total attendance of more than 500,000 people between bikers, vendors, and others:

Sturgis has approximately 6,700 residents, but it doesn’t know it’s considered a “small town” because each year during the Rally when the population nearly doubles that of the entire state, Sturgis steps up and manages one of the oldest and arguably the largest motorcycle gathering in the world. The community has had 78 years to get it right and is successful because of a combination of factors, number one – cooperation. The year-round planning process is facilitated by the Sturgis® Rally Department, a department of the City of Sturgis. However, all city departments to include Police, Fire, Water, Streets, Parks and Finance play a role in making certain the event is managed professionally and competently. Each year is a learning process and part of that process includes changing to meet the needs of the community and our 500,000 visitors and exhibitors, ensuring the event not only continues but continues to flourish.

On July 24 2020, MotorcycleCruiser.com reported that the Sturgis rally was not one of myriad events canceled or postponed in 2020 because of the ongoing pandemic:

We mentioned earlier [in 2020] that plenty of rally-related events outside the city of Sturgis had already said they were all in … that means some of the Rally’s biggest draws – big name bands (though not as big as in previous years), at least half a dozen types of races, custom shows, and more – are all still happening. Surrounding towns and communities are also wide open for business, with most hotels and campgrounds we’ve checked out ready to accept the influx of visitors. And the awesome roads in and around the Black Hills remain ripe and ready for two-wheel exploration, which has always been our favorite part of the Sturgis experience.

But there are new realities to deal with. The pandemic ain’t going anywhere soon, so as with those other moto events, organizers have put new protocols in place to keep people safe. We’ll break those down here as well as offering up suggestions for getting the most out of Sturgis without spiking your anxiety levels. If you choose to go, there are ways to get out in the wind, see the sights, and have a ball. You just need to adapt to the situation; motorcyclists call it situational awareness, and there’s never been a better time to practice it.

Masks, personal protective equipment (PPE), and protocols like social distancing were required of vendors, but merely requested of attendees — the bulk of those in attendance:

The City Council also says it will request that rally-goers be respectful by practicing social distancing and taking personal responsibility by following CDC guidelines. Enhanced safety and sanitization protocols will be carried out for rally-goers in the downtown area.

Vendors will be required to wear personal protective equipment (the city will provide it if they don’t have any) and asked to abide by state and federal protocols related to COVID-19. Parking will still happen on Main Street, but plaza seating and open-container alcohol won’t be allowed. The city has also said that If COVID-19 numbers spike at any time before or during the rally, the mayor can cancel all events immediately.

On August 10 2020, the Billings Gazette reported that 60 percent of residents voted against holding the Sturgis rally in 2020, but the City Council forged ahead and held it anyway. City manager Daniel Ainslie said of the decision:

“There are people throughout America who have been locked up for months and months … So we kept hearing from people saying it doesn’t matter, they are coming to Sturgis. So with that, ultimately the council decided that it was really vital for the community to be prepared for the additional people that we’re going to end up having.”

According to Fox News in an article from August 7 2020, only “a handful” of rally-goers wore face masks, and “Republican Gov. Kristi Noem [had] taken a largely hands-off approach to the pandemic, avoiding a mask mandate and preaching personal responsibility”:

The rally could become the largest gathering since the pandemic began. Organizers were expecting 250,000 people from all over the country to make at the 10-day event. Many bikers were defiant over the restrictions that have altered daily life for most Americans.

“Screw COVID,” read the design on one T-shirt being sold. “I went to Sturgis.”

For Arizona resident Stephen Sample, 66, who rode his bike to the event, the gathering is a break from the mostly homebound routine of the past several months.

“I don’t want to die, but I don’t want to be cooped up all my life either,” he said.

Some of the crowd at Sturgis is composed of retirees and people in the age range deemed most at risk to suffer complications from the virus. South Dakota has had an upward trend in COVID-19 cases but the seven-day average was still only around 84 per day.

On August 9 2020, one of the Sturgis headliners, the lead singer of Smash Mouth, made headlines for mocking concerns about the event’s potential to exacerbate the pandemic:

Smash Mouth’s concert on [August 9 2020] in front of a packed crowd at Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota drew widespread outrage.

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, thousands of bikers poured into the small city of Sturgis on [August 7 2020] for the start of the annual motorcycle rally. More than 250,000 people are expected to attend the 10-day rally, making it one of the largest events to take place during the pandemic … Videos and photos posted to social media showed many in the large crowd seemingly flouting social distancing guidelines Sunday night [August 9 2020]. Most attendees did not appear to be wearing masks.

Event organizers said signs would be posted at all entry points and gathering areas reminding guests to remain socially distant, encouraging the use of face coverings and explaining recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help prevent the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Masks are required for entry and it is recommended they be kept on, according to organizers.

Frontman Steve Harwell told the crowd, “We’re all here together tonight. F— that COVID s—,” one video shows.

Initial Aftermath of the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally

Social media users and news outlets broadly speculated that the rally would lead to a major uptick in cases, among attendees as well as those with whom they came in contact after attending the gathering.

On August 18 2020, Business Insider reported that cell phone location data was being used to map who visited the event, speculating how far infections acquired at the Sturgis Rally might spread:

As COVID-19 cases continue to rise in the US, hundreds of thousands of bikers traveled to a massive annual rally [in August 2020] in Sturgis, South Dakota, where public-health officials have not implemented a lockdown or required people to wear masks.

[…]

Data aggregated by the location-data firm X-Mode Social showed tens of thousands of mobile devices arrived in Sturgis in the first week of August [2020], excluding devices that were already active in the area in the months before the rally. In a video published on Twitter, the data-visualization group Tectonix GEO mapped the movement of phones across the US that were present at the rally.

The firm demonstrated its extrapolated data purportedly gathered from cell phone movement:

An August 26 2020 CNN piece linked 70 cases to the rally, far fewer than the quarter of a million figure later reported. On September 8 2020, the Grand Forks Herald published an article about preliminary research into the aftermath of the rally in Sturgis:

The Sturgis motorcycle rally in South Dakota should be linked to 266,796 of COVID-19 cases reported nationwide between Aug. 2 and Sept. 2 [2020], the researchers said, and should be considered a virus superspreader event, or a situation where a few people spread the disease to a much larger number of people.

[…]

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota could be considered a super-spreader event for COVID-19 and should be linked to about 267,000 cases nationwide at a cost of $12.2 billion, researchers say in a recently released paper.

The researchers from San Diego State University’s Center for Health Economics & Policy Studies published a preliminary version of the paper [in early September 2020] with the IZA – Institute for Labor Economics. The paper, which has not been peer-reviewed, is based on anonymized cellphone location tracking data and is the first known research to estimate the COVID-19 case spread and public health cost of the rally in Sturgis, S.D.

The 10-day motorcycle rally, which ended Aug. 16 [2020], is associated with both local and national surges in COVID-19 cases, particularly in those counties with the highest participation percentage the researchers found.

“We … conclude that local and nationwide contagion from this event was substantial,” the researchers said.

That reporting referenced the use of cell phone data indicating that 19 percent of attendees lived in South Dakota or bordering states, and 72 percent came in from the rest of the United States, “with heavy attendance from Arizona, California, Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Washington and Wyoming.”

However, the news site also noted that public health officials in the state of South Dakota disputed the findings:

But South Dakota health officials cast doubt [after publication] on the researchers’ work.

“The results do not align with what we know of the impacts of the rally among attendees in the state of South Dakota,” said Dr. Joshua Clayton, state epidemiologist, pointing to the 124 known South Dakota cases linked to the Sturgis rally.

Clayton said the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is considering calling for states to submit data on all known COVID-19 cases linked to the Sturgis rally.

IZA Research on the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally as a ‘Super-Spreader Event’

Numbers bandied around on social media and in the news on September 8 2020 originated with IZA, “a nonprofit research institute and the leading international network in labor economics, comprising more than 1,600 scholars from around the world,” and were derived by researchers at San Diego State University’s Center for Health Economics & Policy Studies.

A September 2020 paper (“IZA DP No. 13670: The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19”) was summarized in an abstract on IZA.org as follows, stating that researchers used “anonymized cell phone data” for their extrapolations:

Large in-person gatherings without social distancing and with individuals who have traveled outside the local area are classified as the “highest risk” for COVID-19 spread by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Between August 7 and August 16, 2020, nearly 500,000 motorcycle enthusiasts converged on Sturgis, South Dakota for its annual motorcycle rally. Large crowds, coupled with minimal mask-wearing and social distancing by attendees, raised concerns that this event could serve as a COVID-19 “super-spreader.” This study is the first to explore the impact of this event on social distancing and the spread of COVID-19. First, using anonymized cell phone data from SafeGraph, Inc. we document that (i) smartphone pings from non-residents, and (ii) foot traffic at restaurants and bars, retail establishments, entertainment venues, hotels and campgrounds each rose substantially in the census block groups hosting Sturgis rally events. Stay-at-home behavior among local residents, as measured by median hours spent at home, fell. Second, using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and a synthetic control approach, we show that by September 2 [2020], a month following the onset of the Rally, COVID-19 cases increased by approximately 6 to 7 cases per 1,000 population in its home county of Meade. Finally, difference-in-differences (dose response) estimates show that following the Sturgis event, counties that contributed the highest inflows of rally attendees experienced a 7.0 to 12.5 percent increase in COVID-19 cases relative to counties that did not contribute inflows. Descriptive evidence suggests these effects may be muted in states with stricter mitigation policies (i.e., restrictions on bar/restaurant openings, mask-wearing mandates). We conclude that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally generated public health costs of approximately $12.2 billion.

IZA.org provided access to a longer paper [PDF]; in its “Introduction” section, researchers explained that “though large gathering restrictions have become ubiquitous … there is little empirical evidence on the contagion dangers of large events with ‘super-spreader’ potential, and that “most evidence in support of gathering restrictions has centered around theoretical models of the spread of disease.” They continued, explaining their selection of the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally as an atypically large, poorly managed outlier during the 2020 pandemic:

In this study we examine the 80th Annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, a 10-day event with dozens of concerts, live performances, races, and bike shows that drew over 460,000 individuals to a city with a population of approximately 7,000 located in a county with a population of approximately 26,000. COVID-19 mitigation efforts at the Sturgis Rally were largely left to the “personal responsibility” of attendees, and post-opening day media reports suggest that social distancing and mask-wearing were quite rare in Sturgis.

The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally represents a situation where many of the “worst case scenarios” for superspreading occurred simultaneously: the event was prolonged, included individuals packed closely together, involved a large out-of-town population (a population that was orders of magnitude larger than the local population), and had low compliance with recommended infection countermeasures such as the use of masks. The only large factors working to prevent the spread of infection was the outdoor venue, and low population density in the state of South Dakota.

Researchers further explained their methodology, including how the $12 billion in healthcare costs figure was derived:

Then, using a dose response difference-in-differences model, we find that counties that contributed the highest inflows of Sturgis attendees saw COVID-19 cases rise by 10.7 percent following the Sturgis event relative to counties without any detected attendees. Descriptive evidence suggests some evidence of variation in local COVID-19 spread depending on the stringency of local contagion mitigation policies. We conclude that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally generated substantial public health costs, which we calculate to reach at least $12.2 billion using the statistical value of a COVID-19 case estimated by Kniesner and Sullivan (2020). While we note that this estimate captures the full costs of infections due to the Sturgis rally — and is an overestimate of the externality cost because this number includes COVID-19 infections to individuals who attended the rally (and may have internalized private health risks) — we nonetheless conclude that local and nationwide contagion from this event was substantial.

Researchers also noted that in sporadic large gatherings which occurred in the summer of 2020, an effect was observed in which populations local to any given event often engaged in mitigating behavior, “dampening” the potential spread of the virus to offset an influx of non-residents. In Sturgis, they indicated their findings “suggest that in contrast to prior large gatherings that have been studied (i.e., Tulsa and BLM protests … the local resident population appeared to participate in the events,” which they contend “raises the possibility that the local population may be at risk for COVID-19 spread, especially if mitigating strategies (i.e., mask-wearing, interacting closely with only household members, avoiding crowds) were not undertaken.”

Regarding localized increases in infection rates and accounting for an incubation period, researchers said:

Specifically, after August 16th [2020], we find that COVID-19 cases increase by 2.83 to 3.54 cases per 1,000 population in Meade County relative to its synthetic control. By September 2 [2020], approximately three weeks following the Sturgis event, we find that COVID-19 cases are 6 to 7 cases higher per 1,000 population in Meade County, a 100 to 200 percent increase in cases. This translates to between 177 to 195 more total cases in the County, by the end of the analysis period, as a result of the rally.

[…]

We next turn to an exploration of whether the impact of the Sturgis event extended nationally. That is, we answer the question: did the Motorcycle Rally turn into a super-spreader event?

In the next portion of the paper, researched delved into the 72 percent of attendees who traveled to Sturgis from outside South Dakota or bordering states:

Our findings in column (1) shows that the highest relative inflow counties to Sturgis (outside of the state of South Dakota), which were comprised of counties representing states nationwide, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, Washington, and Wyoming — saw a 10.7 percent increase in COVID-19 cases more than three weeks following the opening of the Sturgis Rally, and about two weeks following the close of the events. Over the same time window, we find that the second highest inflow counties also experienced about a 12.5 percent increase in COVID-19 cases following the events.

Researchers then explained that attendees from states with stronger mitigation policies such as mask mandates may not have gone on to spread the novel pathogen as efficiently as those returning to states with fewer or no policies in place. In the “Conclusion” section, they touched upon the numbers widely referenced in social media posts about the paper:

We are further able to document national spread due to the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, although that spread also appears to have been successfully mitigated by states with strict infection mitigation policies. In counties with the largest relative inflow to the event, the per 1,000 case rate increased by 10.7 percent after 24 days following the onset of Sturgis Pre-Rally Events. Multiplying the percent case increases for the high, moderate-high and moderate inflow counties by each county’s respective pre-rally cumulative COVID-19 cases and aggregating, yields a total of 263,708 additional cases in these locations due to the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. Adding the number of new cases due to the Rally in South Dakota estimated by synthetic control (3.6 per 1,000 population, scaled by the South Dakota population of approximately 858,000) brings the total number of cases to 266,796 or 19 percent of 1.4 million new cases of COVID-19 in the United States between August 2nd 2020 and September 2nd 2020.

Immediately thereafter, researchers provided the accounting behind the “$12 billion in healthcare” costs figure:

If we conservatively assume that all of these cases were non-fatal, then these cases represent a cost of over $12.2 billion, based on the statistical cost of a COVID-19 case of $46,000 estimated by Kniesner and Sullivan (2020). This is enough to have paid each of the estimated 462,182 rally attendees $26,553.64 not to attend. This is by no means an accurate accounting of the true externality cost of the event, as it counts those who attended and were infected as part of the externality when their costs are likely internalized.

Criticism

On September 8 2020, South Dakota Gov. Noem addressed the virally popular research, describing it as “fiction” and “grossly misleading”:

A statement from Noem’s office calls the study “grossly misleading.”

“This report isn’t science; it’s fiction. Under the guise of academic research, this report is nothing short of an attack on those who exercised their personal freedom to attend Sturgis,” Noem said.

She goes on to criticize the media for reporting on “this non-peer reviewed model, built on incredibly faulty assumptions that do not reflect the actual facts and data here in South Dakota.”

A Rapid City Journal article included additional comment from South Dakota public health officials about the paper:

South Dakota Department of Health officials said [on September 7 2020] that they had seen the study, but that they would dispute several data points, such as the projection of hundreds of thousands of cases and the basis of using cell phone data to track the spread of COVID-19.

State epidemiologist Joshua Clayton said it’s important to note that the study is a “white paper” study and hasn’t been peer-reviewed, and that it doesn’t account for “an already increasing trend of cases” in South Dakota and the timing of schools and colleges reopening.

“The results do not align with what we know for the impacts of the rally among attendees in the state,” Clayton said.

State health secretary Kim Malsam-Rysdon said [on September 8 2020] that she would caution reporters against “putting too much stock into models” and pointed to earlier estimates by the state that as many as 600,000 South Dakotans would get COVID-19.

However, reporting about comments by state officials was not clear about how well they understood of the use of cell phone data to track infections:

“We’ve got more people that are becoming sick with COVID-19 from a source that we can’t identify, so I think that’s where it gets problematic to just attribute things like cell phone data” as the source of infections, Malsam-Rysdon said.

Both Malsam-Rysdon and Clayton said they knew cell phone pings from residents of other states and foot traffic increased during the rally, but that they haven’t seen cell phone traffic as a “proven link” to COVID-19 infections or spread.

Clayton said he’s not familiar with the cell phone data source used in the study and what the limitations are for that data.

Officials also appeared to be focused more on localized infection rates, rather than extrapolations based on the 72 percent of out-of-town attendees spreading event-acquired cases after they returned home. When pressed on local rates of infection, officials also did not have precise figures:

State epidemiologist Joshua Clayton did not have data on how many of those students or staff have recovered from COVID-19.

When asked if there’s specific hot spots or outbreaks in schools or colleges that the public should know about, Clayton said cases are reported “across the board” and “virtually among all campuses.”

A featured article by the same news organization published on September 3 2020 — prior to the IZA paper — was headlined, “South Dakota is nation’s top hot spot for COVID-19; 2,143 test positive in last week.” According to that story, South Dakota had become the state with the highest per capita surge in the nation, and that “Iowa and North Dakota follow[ed] the state in hot spot rankings.”

That story further reported that 118 South Dakotans had contracted COVID-19 “as a result of attending the Sturgis motorcycle rally.”

Did the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally Really Generate $12 Billion in Healthcare Costs and Cause More Than 250,000 New Cases?

On September 8 2020, a number of viral social media posts claimed that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally led to over a quarter of a million new cases of COVID-19 (266,796), and generated more than $12 billion in healthcare costs — enough to have paid each of the rally’s estimated 462,182 visitors $26,553.64 not to attend. Those figures were based on extrapolations by researchers at San Diego State University’s Center for Health Economics & Policy Studies and published in a preliminary paper on IZA.org. Although the figures were eye-catching and drove home the risks of a widely-attended, poorly-managed event during the pandemic, they were not yet validated or verified. Since the scope of infection and healthcare costs had yet to be determined (as the researchers themselves said), we rate the claim Unknown.

Update, October 4 2023

Whether the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally was a “super spreader” event was the subject of debate and speculation in 2020, due to what was then the relatively novel nature of the pandemic.

However, a significant amount of scholarly research into the 2020 Sturgis rally and the effects of the unchecked spread of COVID-19 was published in the months and years afterward. As of October 2023, a search for “COVID-19” and “Sturgis Motorcycle Rally” returned no fewer than 363 matches on Google Scholar.

Published research began appearing as early as December 2020, initially measuring cursory data on health outcomes related to the event. By April 2021, the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases published “Widespread Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Transmission Among Attendees at a Large Motorcycle Rally and their Contacts, 30 US Jurisdictions, August–September, 2020,” with an abstract explaining the secondary and tertiary infections associated with it:

The 2020 Sturgis motorcycle rally resulted in widespread transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 across the United States. At least 649 coronavirus disease 2019 cases were identified, including secondary and tertiary spread to close contacts. To limit transmission, persons attending events should be vaccinated or wear masks and practice physical distancing if unvaccinated. Persons with a known exposure should be managed according to their coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination or prior infection status and may include quarantine and coronavirus disease 2019 testing.

In the original version of this page, we reported that Smash Mouth lead singer Steve Harwell “made headlines for mocking concerns about the event’s potential to exacerbate the pandemic.” Harwell died on September 4 2023 at the age of 56; his official cause of death was liver disease.

- A new study says more than 250,000 COVID-19 cases between Aug 2 and Sept 2 came from the Sturgis Rally. That's approx 19 percent of all U.S. cases added last month. The paper's authors also concluded that the rally resulted in $12.2B in public health costs

- New analysis on Covid spread triggered by Sturgis event and implicated in the current epidemic in South Dakota. The estimates in this paper, if confirmed, would place Sturgis as the largest studied super spreading event in U.S.

- We estimate that over 250,000 of the reported cases between August 2 and September 2 are due to the Sturgis Rally. Roughly 19 percent of the national cases during this timeframe.

- This is extraordinary. "We conclude that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally generated public health costs of approximately $12.2 billion.”

- 2 weeks after the Sturgis motorcycle rally, South Dakota has the highest positivity rate (20.9%) in the country.

- Health economists estimate Sturgis resulted in 19% of new U.S. cases last month and cost $12 billion in medical care. Thomas Jefferson said Americans should be free to believe anything they want as long as “it neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” Covid denial does both.

- 1 Rally. 1/2 a million MAGAs. ... 1 month later. 250,000 cases of COVID.

- Sturgis Motorcycle Rally

- Sturgis Motorcycle Rally | FAQ | Attendance in 2020

- Is The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally Still Happening For 2020?

- 60% of Sturgis residents were against a motorcycle rally that brings in thousands but the city approved it. Here's why

- Sturgis rally roars ahead despite coronavirus concerns

- Smash Mouth singer mocks coronavirus pandemic at packed Sturgis Motorcycle Rally concert

- Hundreds of thousands of bikers converged at the massive Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, one of the biggest gatherings during the pandemic. Mapping their phone data shows where they traveled across the US.

- As one of the largest public gatherings since the start of COVID-19, #Sturgis2020 has drawn plenty of media attention. So what does the data say about the real footprint the event may have on our country? We took a look with the help of @xmodesocial and @SafeGraph . Check it out:

- Researchers: Sturgis Motorcycle Rally a 'superspreader event' linked to 267K COVID-19 cases

- Experts feared the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally could be a superspreading event. More than 70 coronavirus cases are already linked to it

- IZA | About

- IZA DP No. 13670: The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19

- The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19

- South Dakota health officials dismiss report calling Sturgis Rally a ‘superspreading event’ with Governor Noem calling it ‘fiction’

- Noem: Study connecting 250,000 COVID-19 cases to Sturgis Rally is 'grossly misleading'

- South Dakota is nation's top hot spot for COVID-19; 2,143 test positive in last week

- The contagion externality of a superspreading event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19

- The spread of COVID-19 shows the importance of policy coordination

- Widespread Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Transmission Among Attendees at a Large Motorcycle Rally and their Contacts, 30 US Jurisdictions, August–September, 2020

- Steve Harwell, Voice of the Band Smash Mouth, Is Dead at 56

- Steve Harwell, the former lead singer of Smash Mouth, dies at 56