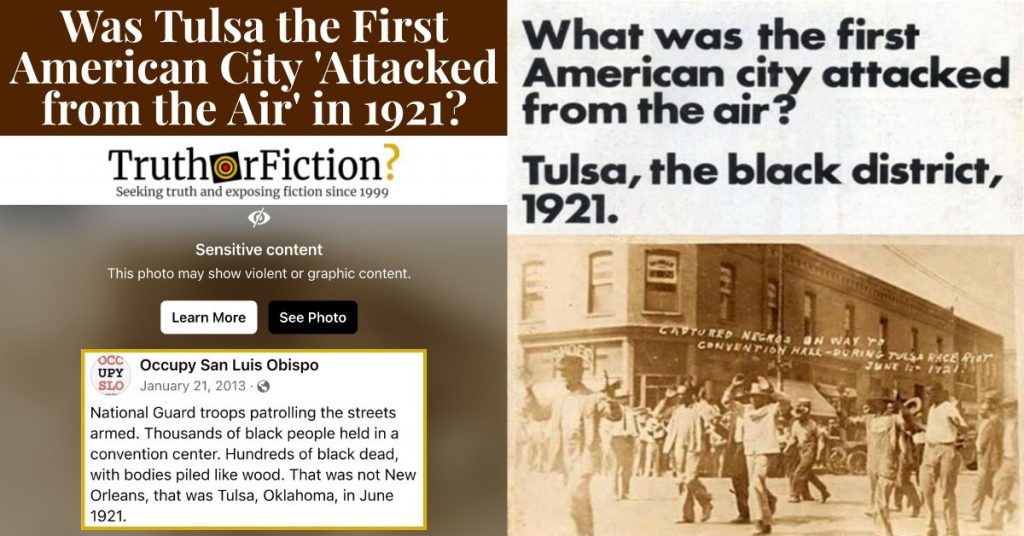

In February 2023, a 2013 Facebook post recirculated, indicating that the first American city to be “attacked from the air” was Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921:

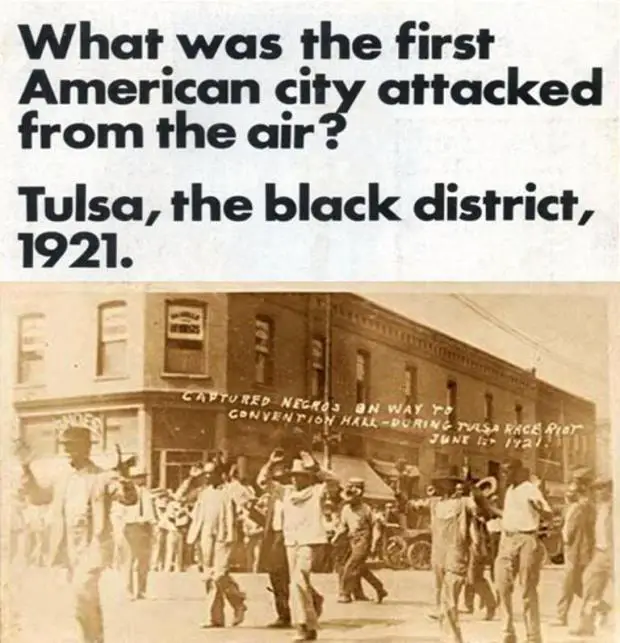

In the image above, a sepia-toned image of people walking with their hands in the air was paired with text. It read:

Fact Check

Claim: “What was the first American city attacked from the air? Tulsa, the black district, 1921.”

Description: A Facebook post asserted that the first American city to experience an air attack was Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the 1921 racial massacre. The city was attacked by private aircraft flown by white men who dropped firebombs.

What was the first American city attacked from the air?

Tulsa, the black district, 1921.

At some point, Facebook hid the image behind a “sensitive content” label. A status update alongside the post provided additional details while reiterating the claim:

National Guard troops patrolling the streets armed. Thousands of black people held in a convention center. Hundreds of black dead, with bodies piled like wood. That was not New Orleans, that was Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June 1921.

On May 30, 1921 a young black man named Dick Rowland, stumbled into a white woman, while entering an elevator. He was accused of assault, and arrested the next day. Newly rich from oil Tulsa, was a Ku Klux Klan town. Rowland was sentenced to be hanged. The Tulsa Tribune called for a “Negro lynching tonight.”

The white mob was surprised when they were met by several dozen armed black men, dressed in their World War I uniforms. This led to a racist three day destruction of the black neighborhood of Greenwood. The Red Cross reported 300 mostly dead black people.

Greenwood called “Little Africa,” was a relatively wealthy community. White mobs, many deputized, destroyed every house, store, church or school. The mob met resistance from an armed black population. Governor Robertson declared martial law. The National Guard arrived with machine gun mounted trucks, and airplanes hovering over Greenwood. It was the first time an American city was bombed from the air, by the US government.

Over 6,000 black people, were round up and held in the convention center and fairgrounds, as long as eight days. The homeless were shuttled into a tent city, where typhoid and malnutrition took over. Blacks were allowed out of the convention center, with a tag, with an employers name. Thosands fled the city.

Attempts to turn Greenwood into an industrial zone were unsuccessful. For several years, it was deprived of paved streets, running water, and garbage collection.

See: Tulsa Reparations Coalition and thank you to Internationalist Group for presenting this story in your newspaper.

In February 2019, we published a general fact check about the 1921 “Tulsa race riot,” in part addressing common claims that the massacre was suppressed or removed from historical texts and references:

[A] meme claimed that in 1921, a race riot in Tulsa claimed the lives of between 300 and 3,000 black people, and that the incident was deliberately elided from history books. Its claims were largely accurate, but the number of deaths was exaggerated. It is true that resentful white residents of Tulsa became enraged when they were prevented from lynching a man who allegedly stepped on a white woman’s foot. In the days following, white Tulsa residents rioted and destroyed a prosperous black community, Greenwood, killing between 50 and 300 citizens. Historians are largely in agreement that the 1921 Tulsa race riot remains underrepresented in historical texts.

With respect to the Facebook post about Tulsa and air strikes from January 2013, elements of our previous fact check examined how and when the long-buried Tulsa massacre drew modern attention. Two of the sources we cited were published 2016 and 2018, respectively:

Much of what we know about the Tulsa riots indeed comes from modern reporting and historical sleuthing. An October 2018 Washington Post article reported that the animus of white residents due to the prosperity of Greenwood was a primary factor in the violence and looting carried out during the riots …

… In May 2016, Smithsonian published a piece on the riots, an article that centered on what it described as a “long-lost” eyewitness account of the brutality and murders. Curator Paul Gardullo discussed the relevance of such an account, as well as the efforts in the late 1990s and early 2000s to make restitution to survivors of the community (attempts which were unsuccessful)[.]

In 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden visited Tulsa to formally acknowledge the incident. In prepared remarks, he noted that no American president had done so in the intervening century:

The events we speak of today took place 100 years ago [as of 2021]. And yet, I’m the first President in 100 years ever to come to Tulsa — (applause) — I say that not as a compliment about me, but to think about it — a hundred years, and the first President to be here during that entire time, and in this place, in this ground, to acknowledge the truth of what took place here.

An initial search for the first American city to be “attacked from the air” led to a Google Highlight contradicting the claim; it linked to a History.com page about Japanese air strikes in Oregon in 1942:

That page had a “first published” date of November 16 2009, before the Tulsa riot was more widely known. It also used “during the war” (World War II), suggesting Google merely chose to highlight an imprecise resource for searchers.

On the website of the National Endowment for the Humanities (neh.gov), an article with the headline “The 1921 Tulsa Massacre” was published in late 2021. After describing an altercation between two people in Tulsa in 1921, the piece continued:

Then according to several chroniclers, “all hell broke loose,” as the mob engaged the retreating Black men in a pitched gun battle that inched its way north toward the Frisco Railroad tracks that separated downtown from Deep Greenwood. The mob broke into downtown (white-owned) pawnshops and hardware stores to steal weapons and bullets. Tulsa law enforcement deputized and armed certain members of the mob. A disguised light-skinned African-American Tulsan overheard an ad hoc meeting of city officials plan a Greenwood invasion that night. Sheriff McCullough, hunkered down in the County Court House, kept Dick Rowland safe as the mob’s fury was aimed at a Negro revolt in Greenwood. While most mob members were not deputized, the general feeling was that they were acting under the protection of the government. The fact that after the disaster none of them were convicted of crimes vindicates that position.

After an all-night battle on the Frisco Tracks, many residents of Greenwood were taken by surprise as bullets ripped through the walls of their homes in the predawn hours. Biplanes dropped fiery turpentine bombs from the night skies onto their rooftops—the first aerial bombing of an American city in history. A furious mob of thousands of white men then surged over Black homes, killing, destroying, and snatching everything from dining room furniture to piggy banks. Arsonists reportedly waited for white women to fill bags with household loot before setting homes on fire. Tulsa police officers were identified by eyewitnesses as setting fire to Black homes, shooting residents and stealing. Eyewitnesses saw women being chased from their homes naked—some with babies in their arms—as volleys of shots were fired at them. Several Black people were tied to cars and dragged through the streets.

A June 12 2020 Tulsa World article (“Tulsa Race Massacre: Was 1921 the first aerial assault on U.S. soil?”) focused on the “first attack by air” angle in advance of a segment set to air on 60 Minutes. It began with a brief transcription from the segment, in which the notion that Tulsa was the first American city attacked by air was framed as new and surprising information:

“The first time Americans were terrorized by an aerial assault was not Pearl Harbor,” a CBS News story says leading up to coverage [in June 2020] of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

“Scott Pelley reports on a race massacre in which an estimated 300 people, mostly African American men, women and children, were killed, and aircraft were used to drop incendiary devices on a black neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The Greenwood Massacre of 1921 has been largely ignored by history, but Pelley finds a Tulsa community seeking to shed more light on what’s been called the worst race massacre in history,” a preview reads for a “60 Minutes” story airing 6 p.m. Sunday [June 14 2020] on CBS.

In that reporting, the paper referenced archival news records showing evidence of the claim — which was, again, part of improperly recorded American history:

… in October 1921 the Chicago Defender published a story in which it said Greenwood had been bombed under orders of “prominent city officials.”

A May 2021 New York Times “interactive” article reported:

The [white] mob indiscriminately shot Black people in the streets. Members of the mob ransacked homes and stole money and jewelry. They set fires, “house by house, block by block,” according to the commission report.

Terror came from the sky, too. White pilots flew airplanes that dropped dynamite over the neighborhood, the report stated, making the Tulsa aerial attack what historians call among the first of an American city.

The numbers presented a staggering portrait of loss: 35 blocks burned to the ground; as many as 300 dead; hundreds injured; 8,000 to 10,000 left homeless; more than 1,470 homes burned or looted; and eventually, 6,000 detained in internment camps.

Finally, a Wikipedia entry for “Aerial bombing of cities” introduced the broad topic by indicating that the practice gained prominence around World War I:

The aerial bombing of cities is an optional element of strategic bombing, which became widespread in warfare during World War I. The bombing of cities grew to a vast scale in World War II, and is still practiced today. The development of aerial bombardment marked an increased capacity of armed forces to deliver ordnance from the air against combatants, military bases, and factories, with a greatly reduced risk to its ground forces. The killing of civilians and non-combatants in bombed cities has variously been a deliberate goal of strategic bombing, or unavoidable collateral damage resulting from intent and technology. A number of multilateral efforts have been made to restrict the use of aerial bombardment so as to protect non-combatants and other civilians.

Following sections described the chronology of airplanes dropping bombs or incendiary devices from the sky. Tulsa’s 1921 massacre had its own section:

Tulsa race massacre

In the United States during the Tulsa race massacre of May 31 – June 1, 1921, private aircraft flown by white men dropped kerosene bombs on the Greenwood neighborhood.

In February 2023 a 2013 Facebook post circulated, claiming that the first American city to be attacked from the air was Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the 1921 race massacre. At the time the post was first published to Facebook, much of the history of the incident was poorly documented — and a Google Highlight in 2023 appeared, falsely, to “debunk” the claim. However, eyewitness accounts and other suppressed historical records indicated that Tulsa residents were indeed subjected to air strikes during the massacre; regional officials then attempted to prevent residents from rebuilding, in an early example of resilience targeting.

- What was the first American city attacked from the air? Tulsa, the black district, 1921. | Facebook

- 1921 Tulsa Race Riot

- Biden’s ‘Black Entrepreneurs’ Speech in Tulsa

- First American city air attack | Google search

- Japanese bomb U.S. mainland | History.com

- The 1921 Tulsa Massacre | NEH.gov

- Tulsa Race Massacre: Was 1921 the first aerial assault on U.S. soil?

- Tulsa Race Massacre

- Aerial bombing of cities | Wikipedia