On July 7 2020, Facebook user David D Smith shared the following post, questioning why coronavirus testing was so invasive, particularly when compared to DNA test cheek swabs:

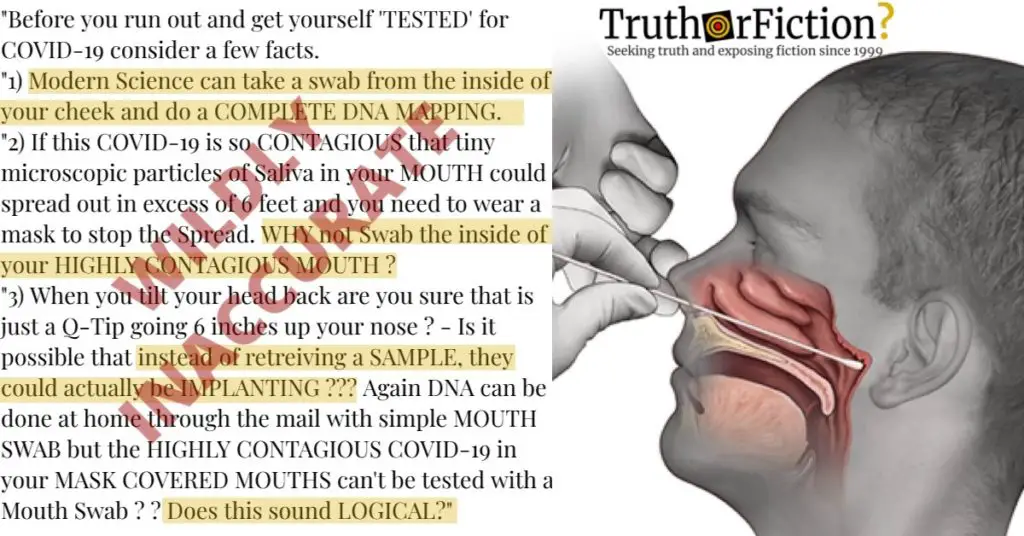

Smith included a shiver-inducing image but no citations, writing:

ATTENTION FRIENDS & FAMILY – Before you run out and get yourself “TESTED” for COVID-19 consider a few facts.

1) Modern Science can take a swab from the inside of your cheek and do a COMPLETE DNA MAPPING.

2) If this COVID-19 is so CONTAGIOUS that tiny microscopic particles of Saliva in your MOUTH could spread out in excess of 6 feet and you need to wear a mask to stop the Spread. WHY not Swab the inside of your HIGHLY CONTAGIOUS MOUTH ?

3) When you tilt your head back are you sure that is just a Q-Tip going 6 inches up your nose ? – Is it possible that instead of retreiving a SAMPLE, they could actually be IMPLANTING SOMETHING ? ? ? Again DNA can be done at home through the mail with simple MOUTH SWAB but the HIGHLY CONTAGIOUS COVID-19 in your MASK COVERED MOUTHS can’t be tested with a Mouth Swab ? ? Does this sound LOGICAL ?

Three points were presented in the post:

- Ubiquitous DNA tests, often done at home, involve a simple cheek swab, also known as a buccal swab. Such tests seem to provide a tremendous amount of information without discomfort associated with COVID-19 tests, making the poster question their necessity;

- COVID-19, described by the poster as “HIGHLY CONTAGIOUS” and spread through aerosolized saliva, ought to be detectable through a similar method;

- The third and final point careened directly into conspiracy theory and just-asking-questions territory, during which the poster mused the tests were invasive because instead of obtaining material to test, they were perhaps impregnating the testing surface with “something” — presumably SARS-CoV-2.

This came with three big, entirely baseless assumptions:

- That home DNA testing and SARS-CoV-2 testing necessarily could be executed in the same fashion, regardless of their underlying purposes and the manner in which samples were evaluated;

- SARS-CoV-2 tests are designed to collect saliva alone and deliberately collect it in a way that is often described as deeply uncomfortable;

- And inherent in this is a conspiracy so vast it involves all test manufacturers in all nations battling the COVID-19 pandemic, and so on and so forth.

The Image, and Nasopharyngeal Swabbing

The image was commonly shared from the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic as a way to discourage people from placing themselves at risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. Ten days after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11 2020, the image showed up on Twitter to dissuade others from incautious behavior:

Also on March 21 2020, the image was shared to Imgur in much the same fashion by u/iCuPiCuOp:

Incidentally, that post involved a comment by u/Inkfinger, who remarked:

Umm I swabbed ten patients today and unless I am doing it wrong, that us 100% not how you stab for corona

(In replies, u/Inkfinger clarified that they had intended to type “swab,” not the much more alarming “stab.”) In the comment’s thread, u/BillFromAmerica countered, describing the illustration as representative of a “nasopharyngeal swab”:

This is a nasopharyngeal swab. I’m an ED nurse and this is how we have been instructed to swab for covid in my hospital.

On March 22 2020, u/Inkfinger published a separate post titled “Setting the Record Straight on Coronavirus Swabbing,” linking back to the original “Ouch” post above along with their comment. They wrote:

Alright, I am going to take a moment here to take ownership of something I said. As a healthcare professional, I take the spread of misinformation very seriously and it is important to me that I clarify my position on this.

Last night, I made a comment [link]

My excuse was, I had just gotten home from a 16hr shift, I was tired, browsing imgur and thought the graphic used was hilarious cause it straight up looks like the poor bastard is being stabbed. I left my comment with one of the best typos of my career and went to bed. Woke up this morning to a shock; I had pissed off the entire medical community on imgur.

I do sincerely want to apologize. I like to think I am a big enough person (or at least try to be) to admit when I am in the wrong. It was never my intention to spread misinformation about how to obtain an adequate specimen or to create any confusion. I would also like to affirm that yes, this is technically the correct way to obtain a nasopharyngeal swab. I would like to assure everyone that all medical staff at my facility have been trained or re-trained on how to properly swab for coronavirus. In the ER we do this all the time especially during flu season but we all agreed to do a 4 hours in-service where we took turns swabbing each other just to make sure everyone knew how to do properly and what it would feel like. I would also like to applaud the imgur community for calling me out on my bullshit because it is very important that we maintain a flow of accurate knowledge. Especially during a crisis…

Discourse on both points cited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance on collecting specimens for SARS-CoV-2 testing. Reviewing that guidance alluded to why COVID-19 tests were so invasive:

Proper collection of specimens is the most important step in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. A specimen that is not collected correctly may lead to false negative test results. The following specimen collection guidelines follow standard recommended procedures.

Reading between the lines helped — and another section explained:

Testing lower respiratory tract specimens is also an option. For patients who develop a productive cough, sputum should be collected and tested for SARS-CoV-2. The induction of sputum is not recommended. When under certain clinical circumstances (e.g., those receiving invasive mechanical ventilation), a lower respiratory tract aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage sample should be collected and tested as a lower respiratory tract specimen.

In layman’s terms, a patient with clear symptoms of illness (coughing up sputum) were likelier to produce a positive test through other means — their infected “aspirate,” or mucus. Diagrams similar to the one in circulation but produced in 2005 were available here [PDF].

A May 28 2020 item in the New England Journal of Medicine explained the procedure and its application during the COVID-19 pandemic, but that information was developed for healthcare professionals, and so it didn’t really delve into why coronavirus testing was so notoriously invasive. However, a June 5 2020 piece by British tabloid The Sun about the prospect of false negatives did put the issue into layman’s terms, quoting several doctors on why COVID-19 tests were so unpleasant for the person being tested:

Dr Andrew Preston, an infectious lung disease expert at the University of Bath, told MailOnline that shallower swabs in the nose and mouth were not as good.

He said: “It’s clear the deeper into the nasopharynx, the better it is picking up the virus.”

Dr Preston added: “We consider it an unsuccessful swab unless the eyes water. We see real, real issues with the sensitivity of the swab if swabbing in nose.

“The further back you go, the more chance you’ve got of getting the virus.”

As for the image’s origin, an April 1 2020 New York Daily News piece attributed it to the company Medivisuals. Medivisuals captioned the illustration:

The nasopharyngeal swab test, which is being used in hospitals and drive-through testing sites across the country, is done by inserting a long plastic stick deep into a person’s nasal cavity and spinning it for a few seconds to absorb a good amount of secretions. The sample is then refrigerated and sent to a lab.

Why COVID-19 Tests Are More Invasive than DNA Testing, and the Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Tests

Although some carriers of SARS-CoV-2 might have viral material sticking around in their upper respiratory tract (meaning it is detectable only through nasopharyngeal swabs), DNA is, by contrast, easy to obtain:

Genetic tests are performed on a sample of blood, hair, skin, amniotic fluid (the fluid that surrounds a fetus during pregnancy), or other tissue. For example, a procedure called a buccal smear uses a small brush or cotton swab to collect a sample of cells from the inside surface of the cheek. The sample is sent to a laboratory where technicians look for specific changes in chromosomes, DNA, or proteins, depending on the suspected disorder. The laboratory reports the test results in writing to a person’s doctor or genetic counselor, or directly to the patient if requested.

That said, not all DNA testing is as simple as a buccal swab. In some cases, it is necessary to draw blood to obtain the proper material for testing.

In the Facebook post we quoted above, the poster characterized a buccal swab as merely collecting saliva. But the link above adds a relevant caveat for individuals preparing for at-home DNA collection, noting that buccal swabbing and saliva collection are not the same, and that confusion about the two can invalidate test results:

People often confuse collecting DNA via cheek cells and collecting DNA via spit. The two are NOT interchangeable processes. If you are doing a paternity test, do not spit on the swabs. Follow directions in the kit and be sure to scrape the insides of the cheeks only. Rubbing the gums may results in collecting excess saliva. If the swabs seem too wet to put in the paper collection envelopes, your instincts are probably correct. Take a few minutes to air-dry the swabs as much as possible by holding them up and waving them in the air prior to putting them in the envelopes.

Another element not addressed in the Facebook post is one that often arises in discussion of managing and understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. Namely that SARS-CoV-2 remained a novel coronavirus, with medical science constantly evolving to meet understanding of the pathogen.

A May 19 2020 NPR segment addressed how the medical view of testing had evolved between the image’s first appearance on social media in March 2020, citing two studies and noting that information was at the time still in flux:

Information is changing quickly and neither [cited] study has been peer reviewed yet, key for acceptance in the scientific community. While these early studies show promise, there still isn’t enough data or information to say with certainty the best test or testing method.

NPR quoted Emily Landon, infectious disease specialist at the University of Chicago, on the subject of COVID-19 testing and its advances in the two previous months. Landon explained that home testing would be a boon, particularly to essential workers who were likelier to be regularly exposed to the virus:

“The holy grail of testing is really something where people can test themselves on a regular basis,” Landon said. “You don’t need staff or people to wear [personal protective equipment] to do the collecting. You don’t need them to be there if you just hand people a sample and they can pick up a kit and take it home.”

Landon envisions a time when essential workers can test themselves daily before heading to work as we wait for a vaccine or cure.

As for why self-testing is allowed now, when it was done only by health care professionals at the start of the pandemic, Landon said this is a routine evolution in how scientists approach new diseases. When there’s a new virus, Landon said guidelines always start out especially conservative. For example, doctors testing for COVID-19 used to collect multiple nose and throat swabs, but also blood and urine samples. As doctors learned more, that changed. They’ve since dropped the blood and urine samples. Now, federal guidelines allow for self-sampling and even at-home tests, which is why different testing sites administer different tests.

“It’s an acknowledgement that there are practicalities,” Landon said. “We may not need the redundancy we were having before, because now we’re confident this one method is good enough.”

That early, better-safe-than-sorry approach evolved as the pandemic entered its second month and researchers were able to glean more information about the virus:

As the federal government has adjusted who can administer a COVID-19 test, they’ve also changed how the test can be conducted. Previously, the preferred test was the nasopharyngeal test, which goes all the way to the back of the nose and is extremely uncomfortable. Doctors and researchers are finding that it’s not always necessary to go back that far.

An early study by UnitedHealth out of Washington state found self-collected nasal swabs, even those that don’t feel like a brain scrape, can be just as reliable as those particularly uncomfortable tests administered by health care workers. Another study by Rutgers University found testing saliva was also extremely reliable.

To answer the Facebook user’s first question about why testing was so invasive, doctors and researchers at the beginning of the pandemic endeavored to produce the most accurate results. As of mid-May 2020, research into the efficacy of other tests — including saliva tests — was underway.

Nevertheless, NPR reported that the depth of the nasopharyngeal swabbing was one of several factors in the constantly-changing COVID-19 testing landscape, observing that the practice was “not just [about] how far back you test within the nasal cavity, but when an individual gets tested compared to when their symptoms began.” Presence of detectable viral matter was, therefore, one of several factors considered when examining the reliability of SARS-CoV-2 tests.

By June 12 2020, HealthDay was reporting about the possible advent of less invasive testing:

Well, the days of “nasopharyngeal” swab tests, administered only by health care workers, may be drawing to a close: New studies find a much more comfortable swab test, performed by patients themselves, works just as well.

One new study of 30 volunteers was conducted by researchers at Stanford University in California. It found near-100% concordance between COVID-19 test results from patient-administered swab tests to the lower nasal passage and the more onerous nurse-delivered test much farther up the nose.

Another study, conducted by UnitedHealth Group in Minnetonka, Minn., found that self-administered swab samples taken from the lower nasal passage delivered over 90% accuracy compared to standard tests that reached into the nasopharynx (where the nasal passages connect with the mouth).

The report indicated that doctors and researchers wanted simpler testing perhaps even more than the public at large:

Dr. Matthew Heinz is a hospitalist and internist at Tucson Medical Center, in Arizona, who’s dealt with COVID-19 testing. Reading over the report from Berke’s team, he noted that shortfalls in staff and supplies for COVID-19 testing “continues to frustrate our response to this viral pandemic.”

While more study is needed to confirm the new findings, they “may point to a role for more self-administered testing going forward,” Heinz said.

A May 21 2020 page from the MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas on SARS-CoV-2 testing reiterated the demand for easier tests — and the need for further inquiry at that point in time. In a section about alternatives to nasopharyngeal swab tests, an answer explained why the invasive test was still preferable — greater accuracy:

Yes, tests can be performed on other specimen types that are less invasive, such as a throat swab. But they are less sensitive than the COVID-19 nasal swab test. Saliva is another specimen type that is being explored, but the jury is still out on that one. The preliminary data look really promising. But we’re still waiting on larger studies to confirm these initial findings.

In addition to nucleic acid testing, which detects a virus’ genetic material, there is also antigen testing, which detects the presence of viral proteins that spur the production of antibodies, or the immune system’s response to invaders.

While antigen tests are quicker, they are also much less sensitive than nucleic acid tests. So, while a positive antigen test is informative, a negative result would need to be confirmed by the more sensitive nucleic acid test.

It’s important to obtain the best possible specimens, so COVID-19 nasal swab testing that includes nucleic acid testing, which is what we do for our patients here at MD Anderson, remains the best option. After all, what’s the point of doing a test, if you can’t get an accurate answer?

As of July 6 2020, a day before the Facebook post was shared, efficacy was still a sticking point in the development of simpler COVID-19 tests. A New York Times article explained that researchers endeavored to strip the process down and make it more accessible, but the work remained in progress:

The latest so-called point-of-care tests, which could be done in a doctor’s office or even at home, would be a welcome upgrade from today’s status quo: uncomfortable swabs that snake up the nose and can take several days to produce results.

The handful of point-of-care devices now on the market are frequently inaccurate. The up-and-coming tests could yield more reliable results, researchers say, potentially leading to on-the-spot testing nationwide. But most of the new contenders are still in early stages, and won’t be available in clinics for months.

Some of the tests in development swap brain-tickling swabs for plastic tubes that collect spit. Others dunk patient samples into chemical cocktails that light up when they detect coronavirus genes. Another type of test identifies coronavirus proteins in minutes, using a cheap device that’s easy to produce in bulk and deploy in low-resource settings.

The same reporting described the original swab test as still being the “gold standard”:

The gold-standard method involves funneling a long, absorbent swab a few inches into the nose until it hits the nasopharynx, the part of the airway where the nasal passage meets the throat and a common target of the coronavirus.

“The moment you see the swab, you’re like, ‘Oh no, my face isn’t that deep,’” said Fernanda Ferreira, a virologist at Harvard University who took a nasopharyngeal swab test in April [2020]. “Turns out it is.”

Another expert explained again why the more invasive COVID-19 test remained so common:

These tests are painless, and avoid putting health care workers in harm’s way. But they aren’t always accurate. “Unfortunately, this virus doesn’t hang around in the nose or throat so much,” said Dr. Ravindra Gupta, a clinical microbiologist at the University of Cambridge.

[…]

Researchers are still gauging how the accuracy of spit tests stacks up against that of the deep nasal swabs, but early results are promising. “You put it in a tube — that’s hard to mess up,” said Anne Wyllie, an epidemiologist at Yale’s School of Public Health who is studying the saliva tests.

Still, the quick tests available now are frequently inaccurate. Although they “ensure we can get an answer faster,” said Dr. Ibukun Akinboyo, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist at Duke University’s School of Medicine, “you lose some sensitivity,” she said. “It’s hard to win at both.”

That article concluded with an important piece of context:

A faster, less invasive test would be nice. But even an unpleasant test is better than no test at all, she said. “If it’s this painful one, so be it.”

Summary: A Quarter of a Million Shares and Counting

In just 48 hours, the Facebook post questioning the invasiveness of COVID-19 testing was approaching a quarter of a million shares. Its third question proposed COVID-19 tests were depositing the virus rather that collecting evidence of its presence — a conspiracy that would literally requiring global compliance (and one easily uncovered should the tests be submitted unused.) The first two points contrasted the seeming ease of buccal or cheek swab DNA tests with nasopharyngeal swabbing for COVID-19, blithely skipping over salient scientific facts to do so.

The answer to why DNA tests were simple cheek swabs and COVID-19 tests were invasive and uncomfortable came down to two primary factors — the varying aims of each test and the presence of biological material. To be effective, COVID-19 tests were, as of July 2020, best designed to collect material as seen in the illustration; by contrast, DNA could be obtained from hair or cheek cells, not necessarily saliva. The second factor was the purpose of DNA tests, which are very often taken for entertainment or ancestry research. COVID-19 tests were to some degree a life-or-death matter, and as of July 2020, the “gold standard” remained a nasopharyngeal swab.

- JAQing Off

- Ouch

- Umm I swabbed ten patients today and unless I am doing it wrong, that us 100% not how you stab for corona

- Setting the Record Straight on Coronavirus Swabbing

- Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens for COVID-19

- NASOPHARYNGEAL SPECIMEN COLLECTION

- How to Obtain a Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimen

- NO ONE NOSE Thousands may have been wrongly told they’re coronavirus-free as 60k DIY swabs a day don’t go deep enough into the nose

- How is genetic testing done?

- Swabs vs. Blood Samples in DNA Paternity Testing

- Stick This Swab Up Your Nose And Twirl It: Self COVID-19 Tests Are On The Rise

- SEE IT: This is how far a swab has to go into your nasal cavity during coronavirus test

- Coronavirus Test: A Swab into the Nasal Cavity

- DIY COVID Tests Work Fine, Less Discomfort

- 10 things to know about COVID-19 testing