MSNBC presenter Brian Williams came under criticism on April 20 2021 after attempting to offer analysis following the murder conviction of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

Footage of the segment posted by RealClearPolitics shows Williams was speaking to network contributor Cedric Alexander, a former police chief for DeKalb County, Georgia.

“We’re gonna have to define public safety in a very different way than what we have in the past,” Alexander said. “And what does that mean, and what do we want police officers to do going forward. And today can be the beginning of that.”

Williams responded:

I’ll do you one better. I’ll say that the George Floyd case has made activists out of average citizens who never imagined that they would be marching on the streets during the summer in a pandemic, but they did. And to combine everything you just said, I hope some small percentage of the mostly young people who have flooded the streets of our country for good reason feeling propelled and compelled to become activists, I hope it occurs to some of them that perhaps a way to change policing is to get involved, change it from the inside, enact the changes to the policies that they’re protesting. That would be a great influx of a population into the policing community.

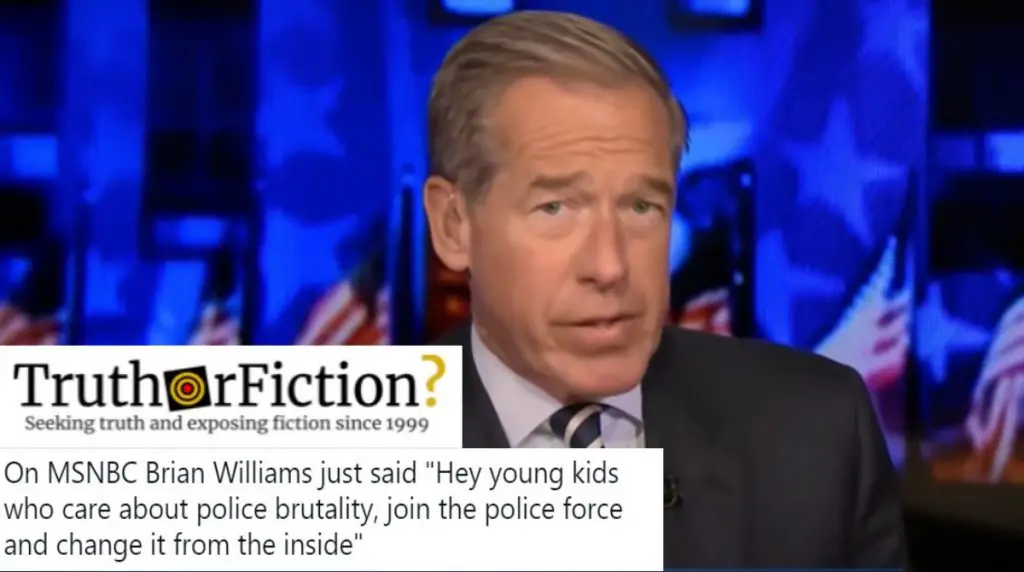

Williams’ remarks began attracting attention after a Twitter account posted a paraphrased version of them:

On MSNBC Brian Williams just said “Hey young kids who care about police brutality, join the police force and change it from the inside”

Williams’ apparent hope regarding internal reform for police departments goes against the historical treatment of officers who do speak up against prejudicial policy; as sociologist Musa al-Gharbi explained in a July 2020 op-ed for The Atlantic:

Police officers in the United States engage in all manner of bad behavior, such as excessive force, sexual misconduct, financial impropriety, and the manipulation of evidence. Holding them to account criminally, civilly, or professionally is extremely difficult, even in cases involving blatant malpractice and misconduct. Yet, even as bad cops evade punishment for wrongdoing, those who stand up to corruption, report negligence or abuse, or decline to comply with bad orders are frequently marginalized, demoted, or outright fired.

Al-Gharbi noted that prior to being arrested for killing Floyd in May 2020, Chauvin already had nearly 20 misconduct complaints on his record.

“This is perhaps one of the most significant yet largely neglected problems with policing in America,” al-Gharbi wrote. “Departments are making an example not of the so-called bad apples, but of the good ones.”

His op-ed is underscored by a 2006 report from the FBI, which concluded that white supremacists had been successfully infiltrating local police departments all over the country. PBS revisited the report ten years later, in October 2016, concluding that little had been done to curtail the persistent and growing issue:

Policing in America has historically had racial implications. The earliest forms of organized law enforcement in the U.S. can be traced to slave patrols that tracked down escaped slaves, and overseers assigned to guard settler communities from Native Americans. In the centuries since, many law enforcement agencies directly participated in antagonizing communities of color, or provided a shield for others who did. But in the 10 years since the FBI’s initial warning, little has changed, Jones said.

Neither the FBI nor state and local law enforcement agencies have established systems for vetting personnel for potential supremacist links, he said. That task is left primarily to everyday citizens and nonprofit organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center, one of few that tracks the growing number of hate groups in America.

“We catch them when we can, which means when we notice someone and check in the database,” said Heidi Beirich, director of the Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center. The group is responsible for exposing an Alabama officer as a member of a white nationalist hate group, League of the South, after he spoke at their national conference in 2013. The officer was later fired.

“Obviously, we do not want people with white supremacist or other extremist views to be in such positions, so it is important to screen them out,” she added.

Williams also made his remark just a week after a New York state judge granted Cariol Horne, a Black woman, the back pay and benefits that were denied to her when she was fired from the Buffalo Police Department. As the New York Times reported, Horne was “reassigned, hit with departmental charges and, eventually, fired” after she stopped a white colleague who was attacking a disabled Black man who had already been handcuffed.

“My vindication comes at a fifteen-year cost, but what has been gained could not be measured,” Horne said after the judge’s decision. “I never wanted another police officer to go through what I had gone through for doing the right thing.”