Beginning in early 2020, many people on social media have likely encountered a “legal warning” advising they not abbreviate the date in a month/day/year (or day/month/year) format in 2020, thanks to the purported ability of all and sundry to alter legally binding documents with wild abandon and change abbreviated dates to any year between 2000 and 2099.

Like many “legal advice” memes, the claim seemed to have its start on Twitter, via a December 31 2019 tweet:

In that initial version, a Twitter user posted the following claim:

Legal advice for 2020:

When writing a date on any document in the upcoming year, 2020, write it in its full format, e.g. 31/01/2020 and not as 31/01/20. Anyone can change it to any date from 31/01/2000 to 31/01/2099. This could render the document invalid.

Right off the bat, there were a number of unstated caveats for the purported legal advice proffered by the user. One is that many dates on important documentation appear in digital formats, leaving users with little choice as to how the year renders. Some involve manually inputting four or two digits specifically, while others feature a drop-down and select menu.

But even forms filled in by hand typically dictate the format of the date in 2020 or any year. Some provide a space for day/month/year, and others month/day/year. Signatures typically involve an adjacent date on signed forms, one of the few common instances of filled-in dates.

Additionally, the user suggested that alteration due to the fact that the prefix for the century’s dates (“20”) and the suffix of the year (also “20”) could invalidate a document. It is not clear whether they intended to claim that abbreviated dates were invalid thanks to that supposed ambiguity, or that subsequent alteration could invalidate the document, or if they were offering some completely different interpretation. (In any event, we found no indication that dates appearing as either day/month/20 or month/day/20 were potentially invalid.)

Myriad Facebook pages shared the “don’t abbreviate 2020 dates” warning as a “heads up,” as “legal advice,” or as “good thinking” at around the same time in late December 2019 and early January 2020:

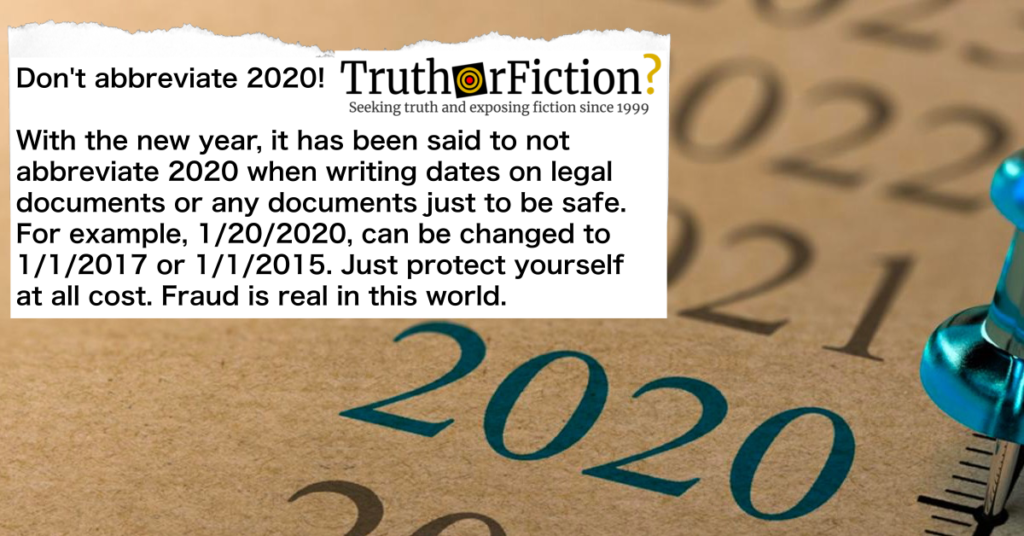

The second of the two posts above was widely shared on personal timelines, and it read:

Just an FYI: With the new year, it has been said to not abbreviate 2020 when writing dates on legal documents or any documents just to be safe. For example, when you write January 1, 2020 as 1/1/20, someone could come behind your date and make it 1/1/2017 or 1/1/2015, etc. Just protect yourself at all cost. Fraud is real in this world.

That particular example involved some hallmarks of urban legend-like crime warnings, such as the vague “it has been said” without indication by whom, a “just to be safe” qualifier, and a closing of “fraud is real” (which sharp-eyed readers might notice in no way substantiated the fears of the meme.)

As is often the case, law enforcement agencies and departments soon started sharing the “legal advice” spreading around, giving it a veneer of authenticity. We’ve seen that happened with the age-old urban legends around drugs and Halloween candy, adding a layer of confusion about the origin of the “advice” being circulated:

By January 3 2020, the warning had changed to the nebulous “authorities are saying,” suggesting that the warning originated not with a random person’s thoughts, but instead was information that had been gleaned by law enforcement or other experts in crime and fraud:

Another police department shared the meme on January 1 2020, urging users to “protect yourself” by not abbreviating the date and attributing the meme to a lawyers’ office:

From there, WIAT turned the meme into a news article, illustrating the obfuscation between police departments sharing memes that a page manager liked, and law enforcement providing information based on facts and evidence. That news organization’s “Don’t abbreviate 2020 when writing out the date” story reported:

The warning: Don’t write the date 1/2/20.

Instead, write out 2020 in full, so it looks like this: 1/2/2020.

Authorities say the date is easily changeable and could ultimately be used against you.

“Example: If you just write 1/1/20, [a scammer] could easily change it to 1/1/2017 (for instance) and now your signature is on an incorrect document,” wrote auditor Dusty Rhodes.

Aside from the embedded meme and a separate embedded tweet, no additional reporting went into the article. It simply stated “people were saying” the date could be altered, presented as proof positive that the claims were legitimate. That tweet utilized modifiers like “possibly,” which didn’t make it into the article:

CNN leapt onto the 2020 date format warning on January 4 2020, with a headline claiming that the advice was “for your own good,” but only bothering to cite unspecified sources who had shared the meme to Facebook and Twitter. CNN also leaned on the urban legend-like “safe than sorry” justification — even as the outlet acknowledged that there was no evidence that the advice had merit:

We’ll just leave you with a PSA that consumer advocates, auditors and police departments around the country have been issuing: When you write a date on a document, don’t shorthand the year 2020 to just “20.” Write out the whole thing (it’s only two more numbers, after all).

It’s still early in the year and there’s no evidence yet that anyone has been scammed in this manner. But it’s better to be safe than sorry.

USA Today also printed Twitter opinions as if they were credible law enforcement warnings. That organization chose the headline “Stop abbreviating 2020. Police say it leaves you open to fraud and could cost you big,” implying that risk existed for anyone abbreviating “2020” to “20.” Most news organizations cited the same Facebook post and tweet, indicating the “advice” wasn’t even widely dispensed until news agencies picked up on a viral meme.

Perhaps the most alarmist version came from WBWN, who seemed to suggest that banks would begin engaging in such behavior to defraud consumers:

By only writing 2-0 in an abbreviated form, scammers could tack on a different year, which can lead to all sorts of problems.

When dealing with loans, if you agreed to make payments on 1/1/20, someone could change the date to 1/1/2019, and come after you for late fees and additional money. It could also be an issue with checks, for example a check dated 1/1/20 could become 1/1/2021, and cause issues with your account if someone tried to cash it again.

Although organizations like WIAT and CNN were quick to pick up on the memes and tweets repeating the “legal advice” about abbreviating 2020, they didn’t seem to read the comments. Right beneath the claims, commenters pointed out some major logical flaws:

“Interesting, how many times did that happen when someone wrote /19”

“Documents could always be easily modified any other year.. slightly easier in 20 I guess but not really any different.. still highly fraudulent lol”

“If you keep records, you know what you write.”

Others indicated that their workplace forms were in day/month/year format (as many are), and commenters repeatedly underscored the absence of logic in the breathless warnings:

You’re not very smart if you think pre-dating a contract, check, or any other legal document is going to get you anything other than a contract, check, or legal document that’s now expired and/or void.

This is a great way to protect yourself from those who want to commit fraud but won’t go as far as using whiteout

Several more commenters expressed their disappointment that a meme with such bad logic was being amplified by both police departments and high-reach news sites:

“It’s astounding the hysteria one tiny police department can cause. There is nothing special about the year 2020 on documents. This could have happened in the years starting with 19[.]”

“this is the … stupidest advice I’ve ever heard. So by adding the other 20 in front you’re suddenly going to make it so the person can’t change the second 20? I don’t understand your theory. You can also change January to July. February to July or January. You can change March to August April to August May to August June to August. There’s so many numbers you can change. The only way to solve this problem is to write it out in letter form. People are so gullible!”

“Gonna call BS on this one unfortunately. Should we not have used “19” for the entirety of last year: eg 3/3/19 because someone could alter it to “3/3/1991(92, 93, 94, through 1998)? Sorry. Sounds like fear mongering here.”

“While you’re doing this, you should also warn people that a car driving at night with its lights off is a gang initiation waiting for someone to flash their high beams.”

“Luckily, it would be impossible for someone to modify a check dated “3/3/2020” to “8/8/2020”. Or “1/15/2020” to “11/15/2020”.

As commenters regularly noted on tweets like the one above, 2019’s abbreviation of “19” could have been modified to any date between 1900 and 1999. Others noted that retention of document copies is common for the reference of all parties involved, rendering a “scam” like the one described virtually useless. Other still pointed out that the advice as given could broadly apply to any document accessible by any person at any time, because anyone with fraudulent intent can modify any document to which they have access — consequences of improper alteration of signed forms were no less in place simply because the format of the year in 2020 was slightly confusing.

In fact, it seemed the same line of thinking could as easily be invoked in reverse — given the ambiguity of 2020 and its abbreviated format, bean counters and auditors might be on closer watch for date-based anomalies. Anyone wishing to dispute the validity of a document could cite the putatively ambiguous year or claim the date was altered by other parties. As all parties are aware that “2020” was abbreviated as “month/day/20,” getting away with altering forms might be even more difficult than in 2019 0r 2021.

In essence, anyone with a mind to attempt fraud — the actual behavior cited in many of the warnings, both by civilians and police department social media managers — doesn’t need a flexible date abbreviation to do so. In an age of Photoshop and, yes, paper corrector such as Wite-Out, altering a binding or otherwise important document is easy.

After a few random social media users got the idea into their heads that abbreviating the year 2020 to “20” in month/day/year formats was an opportunity for rampant scamming, police departments and then news agencies (and fact-checkers) started amplifying warnings about the non-existent “scam” as good advice — which it wasn’t, for several reasons. As pointed out by many, a large number of forms and fields select the format for you — whether it’s YY or YYYY. The “19” at the end of 2019 was just as easy to alter to other years, and there was no rash of backdating being upheld as legally valid. Which leads to the last and final point: fraudulent alteration of forms and instruments could easily be carried out with anyone intending to engage in such behavior with or without an alterable date format.

There is no compelling reason to focus on not abbreviating 2020 to “20,” when people wishing to defraud others could simply alter forms or documents in any manner they wish. If anything, those auditing documents would probably pay close attention to the year format in dates for that specific reason. Tacking “better safe than sorry” and “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” onto viral panics serves only to cloud critical assessment of baseless concerns framed as clever and shared for the sole purpose of racking up Facebook engagement and Twitter likes and retweets.

- Don’t abbreviate 2020 when writing out the date

- Don't abbreviate 2020. It's for your own good

- Police Warn, Don’t Abbreviate 2020 When Writing Out The Date

- Stop abbreviating 2020. Police say it leaves you open to fraud and could cost you big

- Don’t Abbreviate 2020 When Signing Documents, Maine Police Say

- VERIFY: Why you should write the year 2020 instead the shortened "20"