While you may know Dasher and Dancer and Prancer and Vixen, you might not recall that some lore about the most famous reindeer isn’t true at all.

The creation of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” has been linked for years to the death of composer Robert L. May’s wife Evelyn in 1939, with some accounts saying May created the character to comfort their daughter Barbara following the family’s loss.

In 2010, Ace Collins — author of the book Stories Behind the Best-Loved Songs of Christmas — told us that he included that account in his chapter on the story (which originated as a poem before being adapted into a song, and later other mediums) based on a source within the public relations department at Montgomery Wards & Co., where May worked as a copywriter for the company’s popular catalog.

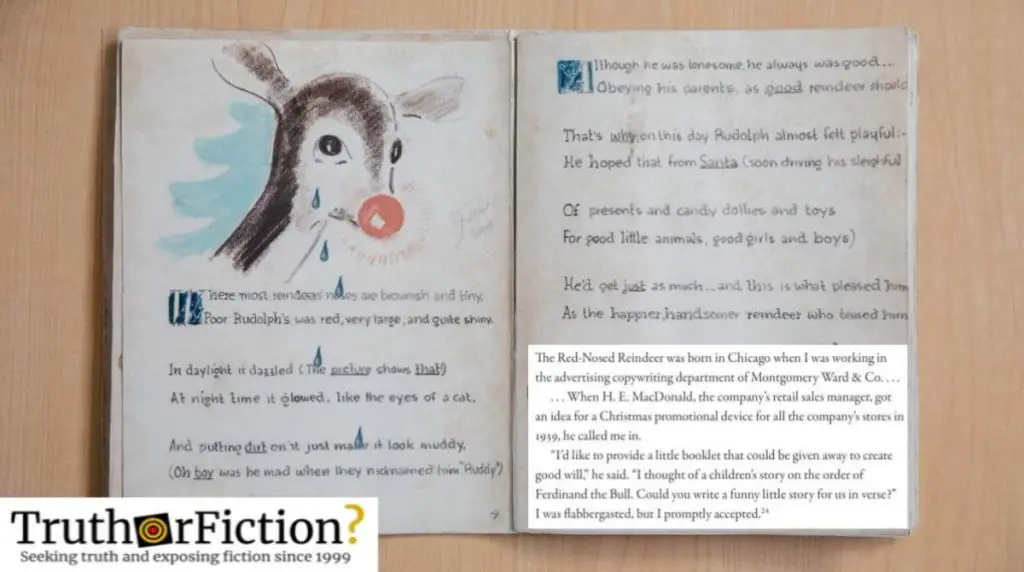

“Though the last few pages of his gift book were stained with tears, Bob would not give up on Rudolph,” Collins wrote. “He knew that his daughter needed the uplifting story now more than ever. He prayed for the strength to finish the project. His efforts were rewarded when Barbara found a completed copy of Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer waiting for her on Christmas morning.”

But five years later, in a story about her father’s work, Barbara May Lewis did not cite her mother’s passing as the inspiration for the story.

“It was his opinion of himself that gave rise to Rudolph, I think, so all the better,” she told NPR.

Ronald D. Lankford’s 2016 book Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, which specifically covers May’s story, further debunks Montgomery Ward’s version of its creation by citing May’s remarks from a 1963 interview for a South Carolina newspaper. May said at the time:

The Red-Nosed Reindeer was born in Chicago when I was working in the advertising copywriting department of Montgomery Ward & Co. …

… When H.E. MacDonald, the company’s retail sales manager, got an idea for a Christmas promotional device for all the company’s stores in Christmas 1939, he called me in.

“I’d like to provide a little booklet that could be given away to create good will,” he said. “I thought of a children’s story on the order of ‘Ferdinand The Bull.’ Could you write a funny little story for us in verse?”

I was flabbergasted, but I gladly accepted.

According to Lankford, the claim that May composed the poem to comfort his daughter dated back to a 1948 article published in Coronet magazine, which claimed that May came up with the story of Rudolph after Barbara asked, “Why isn’t my mommy just like everybody else’s mommy?” The magazine also claimed, falsely, that May read the story at a Montgomery Ward’s holiday party and later sold it to the company for a “modest sum.”

In reality, Evelyn May died in July 1939, as he was writing the story of Rudolph. But as Time magazine reported, her husband refused an offer from the company to put the project on hold, saying: “I needed Rudolph now more than ever. Gratefully I buried myself in the writing.”

“Rudolph” became a hit; the company reportedly distributed more than 2 million free copies of the story upon its publication that year. Crucially, Wards transferred the copyright for “Rudolph” to May on January 1, 1947. Two years later May agreed to let his brother-in-law Johnny Marks adapt the story into a song, which would go on to top the Billboard charts in December 1949 with vocals by Gene Autry.

The song would spur another famous adaptation of the story in 1964, when the company that would come to be known as Rankin/Bass Productions released a stop-motion animation version of “Rudolph” that has become a staple of holiday viewing in the U.S.

Time’s obituary for May reported that by the time of his death in 1971, the formerly struggling copywriter had “received royalties on more than 100 Red-Nosed products” as well as the song.

“While May would never write the great American novel, many believed that what he did write — Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer — was just as important,” Lankford observed.

Update 12/9/2021, 4:18pm PST: This article has been revamped and updated. You can review the original here. -ag